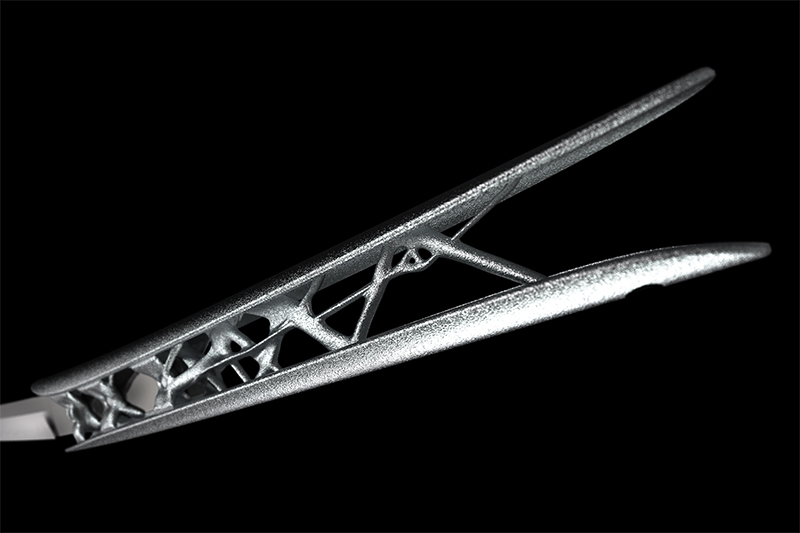

In the project dubbed Tachi (“to stand up” in Japanese), Final Aim uses Autodesk Fusion 360’s Generative Design tools to reshape the iconic Japanese blade handle (right) and display stand (left). Images courtesy of Final Aim.

Reimagining the Iconic Japanese Sword Handle and Display Stand with Generative Design Tools

Japanese designer Yasuhide Yokoi uses Autodesk Fusion 360 to reshape an iconic weapon

Design Exploration and Optimization News

Design Exploration and Optimization Resources

Autodesk

Latest News

June 24, 2022

The forging of a Japanese sword is a subtle and careful process, an art that has developed over the centuries as much in response to stylistic and aesthetic considerations as to technical improvements. To fashion these blades, the smith not only must possess physical strength, but also patience, dexterity, and a refined eye for the limits of the material and the beauty of a finished sword.

—Edward Hunter, Department of Arms and Armor, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

When Yasuhide (Yasu) Yokoi, Chief Design Officer and Cofounder of Final Aim, began using generative design (GD) tools in Autodesk Fusion 360 to reimagine the form of the Japanese sword handle, called tsuka, he knew he was wading into a sacred territory, a traditional craft dating back to the Heian Period (794 to 1185). But Yasu, born in Japan and raised in Australia, is a designer straddling two words, equally devoted to tonkotsu (pork bone-flavor) Ramen and sushi as well as machine learning and additive manufacturing.

Most Japanese swordsmiths would be reluctant to work with computer-driven design methods, but fortunately, Yasu found a rare exception in Kunihira Kawachi, a 15th-generation swordsmith and the author of The Art of the Japanese Sword (coauthor Masao Manabe, Floating World Editions, 2006). “He was eager to try some new, innovative approaches,” recalled Yasu. With the swordsmith tempering the blade, Yasu began working on the grip and the display stand.

Working With a New Method

Yasu himself is relatively new to generative design. “I’ve been fiddling with it for the past one or two years as a hobby, looking into algorithmic design and lattice structures,” he said. He has investigated various software packages offering these tools but, eventually, he settled on Autodesk Fusion 360 as his choice for daily design activities.

Traditionally, the Japanese sword handle is made of wood, wrapped in the stingray fish’s bumpy skin. For added grip, the handle is wrapped in strands of cotton or silk, forming crisscrossing patterns.

To use generative design, Yasu needed to define the design space and input parameters. “The grip needs a certain amount of surface area,” Yasu explained. Using his experience designing DSLR cameras at Nikon, he figured out the ideal region for a firm grip. “Then I had to consider the exerted forces and their directions, the rotational forces, and my material choices,” he recalled. He picked Aluminum because “It’s a conventional material we can easily buy,” he said. “We also tried it with plastics and nylon-based materials, but in terms of weight and aesthetic, Aluminum was the best.”

For the balanced feel of the sword, figuring out the center of gravity is an important part. Currently, off-the-shelf generative design tools seldom include the option to define the center of gravity or use it as an input parameter, so Yasu has to figure it out using his designer’s instinct and physics.

Battling Preconceived Notions

Apart from the technological challenges, Yasu had to confront the established ideas of aesthetics in the field. “There are long-held ideas of the ideal curvatures, how the handle blend with the blade to form a cohesive whole, and how you’re supposed to display the finished piece,” he said. “So I had to strike a balance. I’m departing from tradition, but I cannot be too disruptive either,” he reasoned. “And generative design doesn’t yet have a way to give me guidance on what that ideal aesthetic balance is supposed to be.”

When he knew he had reached the software’s limit, he sought input from the sword-maker who embodies hundreds of years of ancient wisdom, passed down from the previous generations. Consultation with the master craftsman over email exchanges and shared photos brought him to the final design.

As a technology, generative design is highly accessible, but, at least for now, the method is fighting an uphill battle, Yasu said. “People have preconceived ideas of what industrial design is supposed to look like, so when they see algorithm-driven design, they think it’s too spooky, even if it’s much more functional.”

Yasu wondered if people’s perception could also be part of the input parameters in generative design tools to prevent the software from spitting out extreme forms that, based on the prevalent sense of aesthetic, the general consumers are bound to reject.

“But I’m not a programmer, so I don’t know if it’s possible,” he said with a laugh.

Yasu first unveiled the project’s outcome at Autodesk Accelerate (May 2022), an industry event hosted by Autodesk. The finished art piece dubbed tachi (to stand up, in Japanese) is currently housed at the Tokyo-based Studio Shikumi Inc., a collaborator in the project.

刀匠 河内國平の刀剣と、最新のAI(人工知能)とWeb3テクノロジーを融合させた日本刀のアート作品「TACHI」を発表します。本作はデザインとデジタル製造業領域を中心にWeb3事業をグローバルに展開するFinal Aimとのコラボレーションプロジェクトによって生まれました。#刀剣 https://t.co/CxOK4kylaN

— studio shikumi (@studio_shikumi) June 9, 2022

More Autodesk Coverage

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at kennethwong@digitaleng.news or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE